CloudMLDevOps

Git

What is the command to write a commit message in Git?

What is difference between Git vs SVN?

How to undo the most recent commits in Git?

What is Git fork? What is difference between fork, branch and clone?

What is the difference between “git pull” and “git fetch”?

What’s the difference between a “pull request” and a “branch”?

How does the Centralized Workflow work?

You need to update your local repos. What git commands will you use?

Tell me the difference between HEAD, working tree and index, in Git?

When should I use “git stash”?

How to revert previous commit in git?

Explain the advantages of Forking Workflow

Could you explain the Gitflow workflow?

Write down a sequence of git commands for a “Rebase Workflow”

How to remove a file from git without removing it from your file system?

What is difference between “git stash pop” and “git stash apply”?

Can you explain what “git reset” does in plain english?

Write down a git command to check difference between two commits

How to amend older Git commit?

What git command do you need to use to know who changed certain lines in a specific file?

When do you use “git rebase” instead of “git merge”?

Do you know how to easily undo a git rebase?

What is the command to write a commit message in Git?

Use:

git commit -a

-a on the command line instructs git to commit the new content of all tracked files that have been modified. You can use

git add <file>

or

git add -A

before git commit -a if new files need to be committed for the first time.

What is difference between Git vs SVN?

The main point in Git vs SVN debate boils down to this: Git is a distributed version control system (DVCS), whereas SVN is a centralized version control system.

Source

- https://medium.com/@gauravtaywade/15-interview-questions-about-git-that-every-developer-should-know-bcaf30409647

What is Git?

Git is a Distributed Version Control system (DVCS). It can track changes to a file and allows you to revert back to any particular change.

Its distributed architecture provides many advantages over other Version Control Systems (VCS) like SVN one major advantage is that it does not rely on a central server to store all the versions of a project’s files.

How to undo the most recent commits in Git?

$ git commit -m "Something terribly misguided"

$ git reset HEAD~ # copied the old head to .git/ORIG_HEAD

<< edit files as necessary >>

$ git add ...

$ git commit -c ORIG_HEAD # will open an editor, which initially contains the log message from the old commit and allows you to edit it

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/927358/how-to-undo-the-most-recent-commits-in-git

What is Git fork? What is difference between fork, branch and clone?

- A fork is a remote, server-side copy of a repository, distinct from the original. A fork isn’t a Git concept really, it’s more a political/social idea.

- A clone is not a fork; a clone is a local copy of some remote repository. When you clone, you are actually copying the entire source repository, including all the history and branches.

- A branch is a mechanism to handle the changes within a single repository in order to eventually merge them with the rest of code. A branch is something that is within a repository. Conceptually, it represents a thread of development.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/3329943/git-branch-fork-fetch-merge-rebase-and-clone-what-are-the-differences/

What is the difference between “git pull” and “git fetch”?

In the simplest terms, git pull does a git fetch followed by a git merge.

-

When you use

pull, Git tries to automatically do your work for you. It is context sensitive, so Git will merge any pulled commits into the branch you are currently working in.pullautomatically merges the commits without letting you review them first. If you don’t closely manage your branches, you may run into frequent conflicts. -

When you

fetch, Git gathers any commits from the target branch that do not exist in your current branch and stores them in your local repository. However, it does not merge them with your current branch. This is particularly useful if you need to keep your repository up to date, but are working on something that might break if you update your files. To integrate the commits into your master branch, you usemerge.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/292357/what-is-the-difference-between-git-pull-and-git-fetch

What’s the difference between a “pull request” and a “branch”?

-

A branch is just a separate version of the code.

-

A pull request is when someone take the repository, makes their own branch, does some changes, then tries to merge that branch in (put their changes in the other person’s code repository).

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/19059838/whats-the-difference-between-a-pull-request-and-a-branch

How does the Centralized Workflow work?

The Centralized Workflow uses a central repository to serve as the single point-of for all changes to the project. The default development branch is called master and all changes are committed into this branch.

Developers start by cloning the central repository. In their own local copies of the project, they edit files and commit changes. These new commits are stored locally.

To publish changes to the official project, developers push their local master branch to the central repository. Before the developer can publish their feature, they need to fetch the updated central commits and rebase their changes on top of them.

Compared to other workflows, the Centralized Workflow has no defined pull request or forking patterns.

Source

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/comparing-workflows

You need to update your local repos. What git commands will you use?

It’s a two steps process. First you fetch the changes from a remote named origin:

git fetch origin

Then you merge a branch master to local:

git merge origin/master

Or simply:

git pull origin master

If origin is a default remote and ‘master’ is default branch, you can drop it eg. git pull.

Source

- https://samwize.com/2012/10/30/common-git-usage/

You need to rollback to a previous commit and don’t care about recent changes. What commands should you use?

Let’s say you have made mulitple commits, but the last few were bad and you want to rollback to a previous commit:

git log // lists the commits made in that repository in reverse chronological order

git reset --hard <commit-sha1> // resets the index and working tree

Source

- https://gist.github.com/chyld/4570933

What is “git cherry-pick”?

The command git cherry-pick is typically used to introduce particular commits from one branch within a repository onto a different branch. A common use is to forward- or back-port commits from a maintenance branch to a development branch.

This is in contrast with other ways such as merge and rebase which normally apply many commits onto another branch.

Consider:

git cherry-pick <commit-hash>

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/9339429/what-does-cherry-picking-a-commit-with-git-mean

Tell me the difference between HEAD, working tree and index, in Git?

- The working tree/working directory/workspace is the directory tree of (source) files that you see and edit.

- The index/staging area is a single, large, binary file in

/.git/index, which lists all files in the current branch, their sha1 checksums, time stamps and the file name - it is not another directory with a copy of files in it. - HEAD is a reference to the last commit in the currently checked-out branch.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/3689838/whats-the-difference-between-head-working-tree-and-index-in-git

When should I use “git stash”?

The git stash command takes your uncommitted changes (both staged and unstaged), saves them away for later use, and then reverts them from your working copy.

Consider:

$ git status

On branch master

Changes to be committed:

new file: style.css

Changes not staged for commit:

modified: index.html

$ git stash

Saved working directory and index state WIP on master: 5002d47 our new homepage

HEAD is now at 5002d47 our new homepage

$ git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

The one place we could use stashing is if we discover we forgot something in our last commit and have already started working on the next one in the same branch:

# Assume the latest commit was already done

# start working on the next patch, and discovered I was missing something

# stash away the current mess I made

$ git stash save

# some changes in the working dir

# and now add them to the last commit:

$ git add -u

$ git commit --ammend

# back to work!

$ git stash pop

Source

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/saving-changes/git-stash

How to revert previous commit in git?

Say you have this, where C is your HEAD and (F) is the state of your files.

(F)

A-B-C

↑

master

- To nuke changes in the commit:

git reset --hard HEAD~1Now B is the HEAD. Because you used –hard, your files are reset to their state at commit B.

- To undo the commit but keep your changes:

git reset HEAD~1Now we tell Git to move the HEAD pointer back one commit (B) and leave the files as they are and

git statusshows the changes you had checked into C. - To undo your commit but leave your files and your index

git reset --soft HEAD~1When you do

git status, you’ll see that the same files are in the index as before.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/927358/how-to-undo-the-most-recent-commits-in-git

Explain the advantages of Forking Workflow

The Forking Workflow is fundamentally different than other popular Git workflows. Instead of using a single server-side repository to act as the “central” codebase, it gives every developer their own server-side repository. The Forking Workflow is most often seen in public open source projects.

The main advantage of the Forking Workflow is that contributions can be integrated without the need for everybody to push to a single central repository that leads to a clean project history. Developers push to their own server-side repositories, and only the project maintainer can push to the official repository.

When developers are ready to publish a local commit, they push the commit to their own public repository—not the official one. Then, they file a pull request with the main repository, which lets the project maintainer know that an update is ready to be integrated.

Source

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/comparing-workflows/forking-workflow

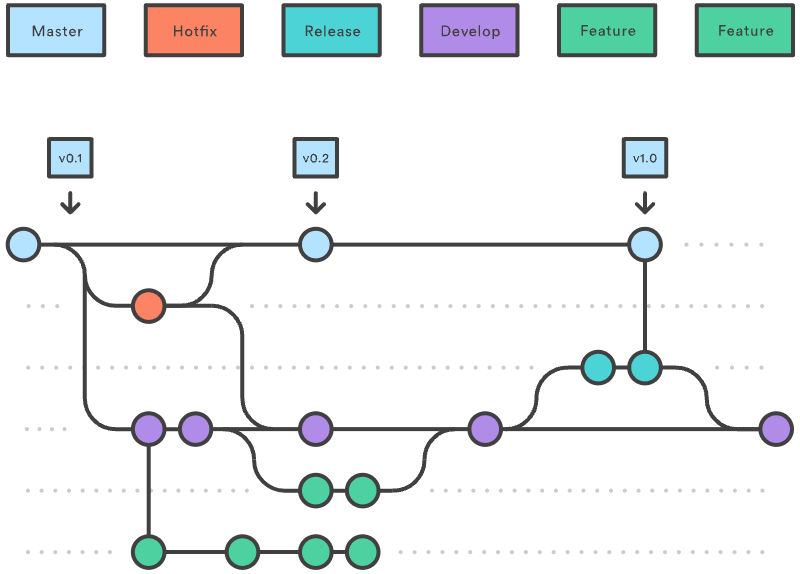

Could you explain the Gitflow workflow?

Gitflow workflow employs two parallel long-running branches to record the history of the project, master and develop:

- Master - is always ready to be released on LIVE, with everything fully tested and approved (production-ready).

-

Hotfix - Maintenance or “hotfix” branches are used to quickly patch production releases. Hotfix branches are a lot like release branches and feature branches except they’re based on

masterinstead ofdevelop. - Develop - is the branch to which all feature branches are merged and where all tests are performed. Only when everything’s been thoroughly checked and fixed it can be merged to the

master. - Feature - Each new feature should reside in its own branch, which can be pushed to the

developbranch as their parent one.

Source

- https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials/comparing-workflows/gitflow-workflow

Write down a sequence of git commands for a “Rebase Workflow”

Rebasing replays changes from one line of work onto another in the order they were introduced, whereas merging takes the endpoints and merges them together.

- Create a feature branch

$ git checkout -b feature - Make changes on the feature branch

$ echo "Bam!" >>foo.md $ git add foo.md $ git commit -m 'Added awesome comment' - Fetch upstream repository

$ git fetch upstream - Rebase changes from feature branch onto upstream/master

$ git rebase upstream/master5.Rebase local master onto feature branch

$ git checkout master $ git rebase feature - Push local master to upstream

$ git push upstream master

Rebasing gives you a clean linear commit history and creates non-obvious benefits to your project if used diligently. Think of it as taking a line of work and pretending it always started at the very latest revision.

Source

- http://kensheedlo.com/essays/why-you-should-use-a-rebase-workflow/

What is the “HEAD” in Git?

HEAD is a ref (reference) to the currently checked out commit.

In normal states, it’s actually a symbolic ref to the branch you have checked out - if you look at the contents of .git/HEAD you’ll see something like “ref: refs/heads/master”. The branch itself is a reference to the commit at the tip of the branch. Therefore, in the normal state, HEAD effectively refers to the commit at the tip of the current branch.

It’s also possible to have a detached HEAD. This happens when you check out something besides a (local) branch, like a remote branch, a specific commit, or a tag. The most common place to see this is during an interactive rebase, when you choose to edit a commit. In detached HEAD state, your HEAD is a direct reference to a commit - the contents of .git/HEAD will be a SHA1 hash.

Generally speaking, HEAD is just a convenient name to mean “what you have checked out” and you don’t really have to worry much about it. Just be aware of what you have checked out, and remember that you probably don’t want to commit if you’re not on a branch (detached HEAD state) unless you know what you’re doing (e.g. are in an interactive rebase).

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/2529971/what-is-the-head-in-git

How to remove a file from git without removing it from your file system?

If you are not careful during a git add, you may end up adding files that you didn’t want to commit. However, git rm will remove it from both your staging area (index), as well as your file system (working tree), which may not be what you want.

Instead use git reset:

git reset filename # or

echo filename >> .gitingore # add it to .gitignore to avoid re-adding it

This means that git reset <paths> is the opposite of git add <paths>.

Source

- https://www.codementor.io/citizen428/git-tutorial-10-common-git-problems-and-how-to-fix-them-aajv0katd

What is difference between “git stash pop” and “git stash apply”?

git stash pop throws away the (topmost, by default) stash after applying it, whereas git stash apply leaves it in the stash list for possible later reuse (or you can then git stash drop it).

This happens unless there are conflicts after git stash pop (say your stashed changes conflict with other changes that you’ve made since you first created the stash), in this case, it will not remove the stash, behaving exactly like git stash apply.

Another way to look at it: git stash pop is git stash apply && git stash drop.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/15286075/difference-between-git-stash-pop-and-git-stash-apply

Can you explain what “git reset” does in plain english?

In general, git reset function is to take the current branch and reset it to point somewhere else, and possibly bring the index and work tree along.

- A - B - C (HEAD, master)

# after git reset B (--mixed by default)

- A - B (HEAD, master) # - C is still here (working tree didn't change state), but there's no branch pointing to it anymore

Remeber that in git you have:

- the HEAD pointer, which tells you what commit you’re working on

- the working tree, which represents the state of the files on your system

- the staging area (also called the index), which “stages” changes so that they can later be committed together

So consider:

git reset --softmoves HEAD but doesn’t touch the staging area or the working tree.git reset --mixedmoves HEAD and updates the staging area, but not the working tree.git reset --mergemoves HEAD, resets the staging area, and tries to move all the changes in your working tree into the new working tree.git reset --hardmoves HEAD and adjusts your staging area and working tree to the new HEAD, throwing away everything.

Use cases:

- Use

--softwhen you want to move to another commit and patch things up without “losing your place”. It’s pretty rare that you need this. - Use

--mixed(which is the default) when you want to see what things look like at another commit, but you don’t want to lose any changes you already have. - Use

--mergewhen you want to move to a new spot but incorporate the changes you already have into that the working tree. - Use

--hardto wipe everything out and start a fresh slate at the new commit.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/2530060/can-you-explain-what-git-reset-does-in-plain-english

Write down a git command to check difference between two commits

git diff allows you to check the differences between the branches or commits. If you type it out automatically, you can checkout the differences between your last commit and the current changes that you have.

git diff <branch_or_commit_name> <second_branch_or_commit>

How to amend older Git commit?

git rebase -i HEAD^^^

Now mark the ones you want to amend with edit or e (replace pick). Now save and exit.

Now make your changes, then:

git add -A

git commit --amend --no-edit

git rebase --continue

If you want to add an extra delete remove the options from the commit command. If you want to adjust the message, omit just the --no-edit option.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/8824971/how-to-amend-older-git-commit/18150592#18150592

What git command do you need to use to know who changed certain lines in a specific file?

Use git blame - a little feature in git that allows you to see who wrote what in the repository. If you want to know who changed certain lines, you can use the -L flag to figure out who changed those lines. You can use the command:

git blame -L <line-number>,<ending-linenumber> <filename>

Source

- https://github.com/mikeizbicki/ucr-cs100/tree/2015winter/textbook/tools/git/advanced-git

When do you use “git rebase” instead of “git merge”?

Both of these commands are designed to integrate changes from one branch into another branch - they just do it in very different ways.

Consider before merge/rebase:

A <- B <- C [master]

^

\

D <- E [branch]

after git merge master:

A <- B <- C

^ ^

\ \

D <- E <- F

after git rebase master:

A <- B <- C <- D <- E

With rebase you say to use another branch as the new base for your work.

When to use:

- If you have any doubt, use merge.

- The choice for rebase or merge based on what you want your history to look like.

More factors to consider:

- Is the branch you are getting changes from shared with other developers outside your team (e.g. open source, public)? If so, don’t rebase. Rebase destroys the branch and those developers will have broken/inconsistent repositories unless they use

git pull --rebase. - How skilled is your development team? Rebase is a destructive operation. That means, if you do not apply it correctly, you could lose committed work and/or break the consistency of other developer’s repositories.

- Does the branch itself represent useful information? Some teams use the branch-per-feature model where each branch represents a feature (or bugfix, or sub-feature, etc.) In this model the branch helps identify sets of related commits. In case of branch-per-developer model the branch itself doesn’t convey any additional information (the commit already has the author). There would be no harm in rebasing.

- Might you want to revert the merge for any reason? Reverting (as in undoing) a rebase is considerably difficult and/or impossible (if the rebase had conflicts) compared to reverting a merge. If you think there is a chance you will want to revert then use merge.

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/804115/when-do-you-use-git-rebase-instead-of-git-merge

Do you know how to easily undo a git rebase?

The easiest way would be to find the head commit of the branch as it was immediately before the rebase started in the reflog

git reflog

and to reset the current branch to it (with the usual caveats about being absolutely sure before reseting with the --hard option).

Suppose the old commit was HEAD@{5} in the ref log:

git reset --hard HEAD@{5}

Also rebase saves your starting point to ORIG_HEAD so this is usually as simple as:

git reset --hard ORIG_HEAD

Source

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/134882/undoing-a-git-rebase